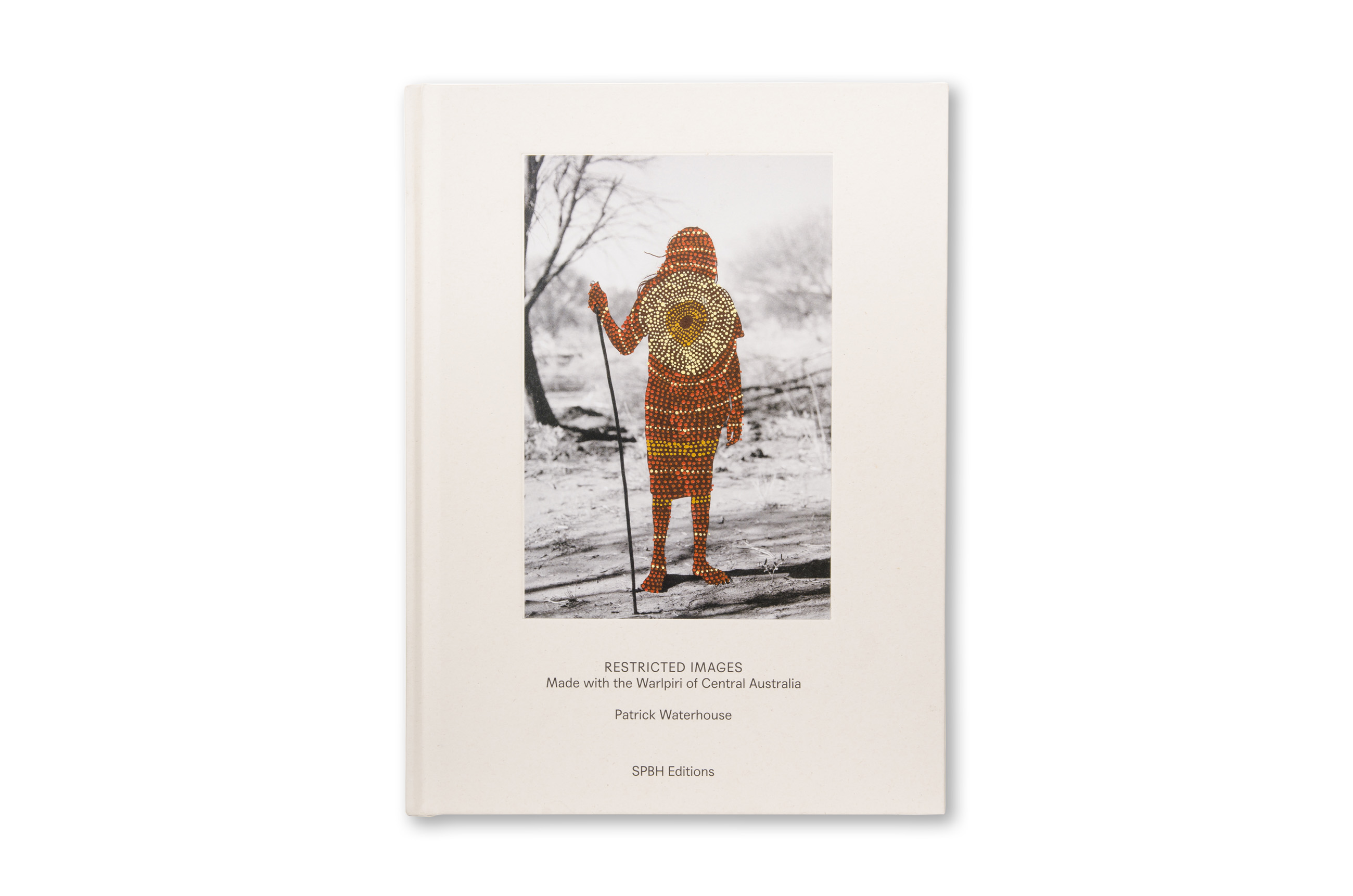

Restricted Images

Confronting flawed representations of the past

British artist

Patrick Waterhouse has always been fascinated by history, how the past is represented, the conflicting stories that are told, the question of what gets included and what is rubbed out.

He remembers what a revelation it was to discover that different versions of history existed outside the prescribed learning of the classroom. For example, the Francis Drake from Waterhouse’s history lessons at school, an Elizabethan explorer whose daring exploits helped to defeat the Spanish Armada and save England, was quite different to the Drake depicted in Spanish history books. That figure was not a hero but a slave trader and pirate who plundered Spanish ships returning from the colonies in South America.

“It was one of those moments where you realize history is very much in the way the story is told,” Waterhouse said in an interview at his east London studio, where he showed artwork from his latest collection, a beautifully subtle response to flawed representations of the past.

Published by

SPBH Editions, Restricted Images:

Made with the Warlpiri of Central Australia by Patrick Waterhouse was created in collaboration with Indigenous communities in Australia, and is his first major work since winning the Deutsche Borse Photography Prize for Ponte City in 2015. “I was interested in finding communities that were marginalized from the way history was being told by great institutions and having a conversation with them about this,” said Waterhouse, whose work spans photography, drawing, graphic design and other disciplines.

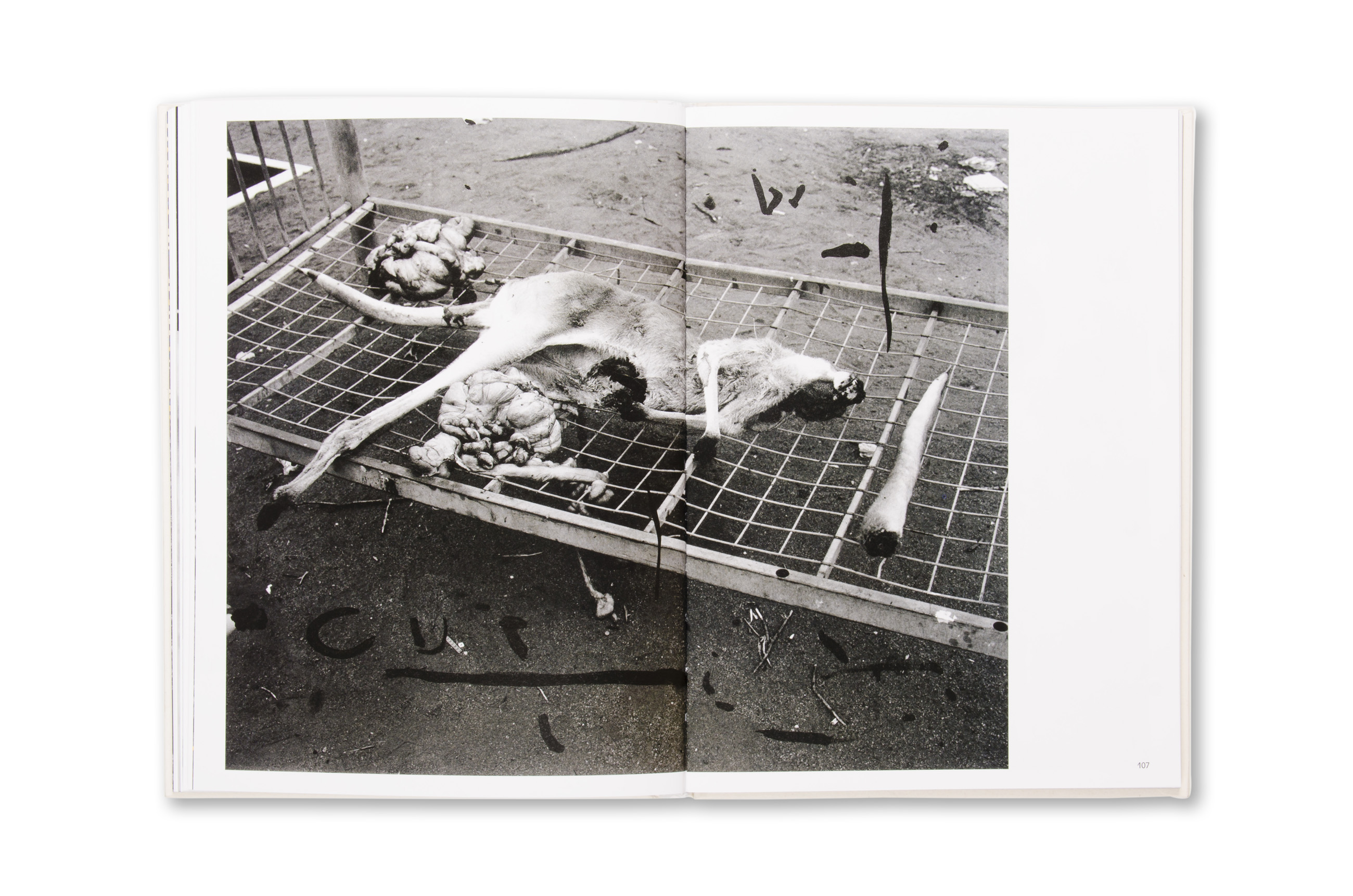

The project began to take shape after Waterhouse visited the Australian outback for the first time in 2011. Travelling through the vast desert, the artist’s encounters with different Aboriginal communities sparked an interest in how Indigenous groups had been represented historically, particularly by 19th century anthropologists such as Baldwin Spencer and Francis James Gillen, whose seminal book

The Native Tribes of Central Australia documents Aboriginal culture, rituals and ceremonies in unprecedented detail. The duo won acclaim for their pioneering work, but some of their actions, including stealing sacred stones and advocating the separation of Aboriginal children of mixed descent from the rest of the Aboriginal population, do not stand up to modern day scrutiny.

“It’s complicated. For the time in which they lived, they were amazingly progressive and reached outside of their culture and really saw Aboriginal people as having a complex belief system. At the same time, when you look at it now, it’s deeply problematic. They used language which is in no way acceptable. They were being given access to information and knowledge by people who didn’t know how it would be disseminated and didn’t know the implications of the camera,” Waterhouse said.

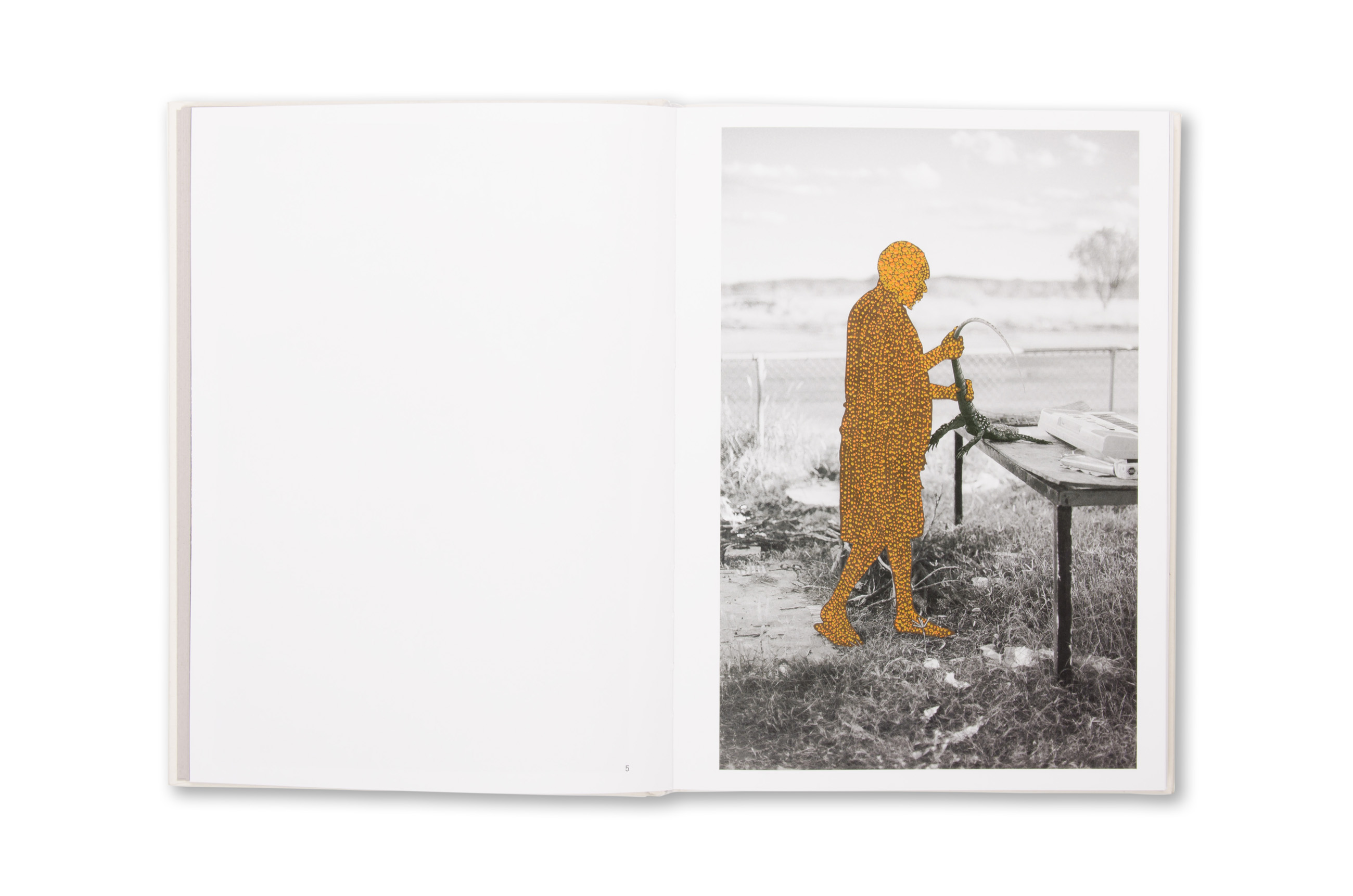

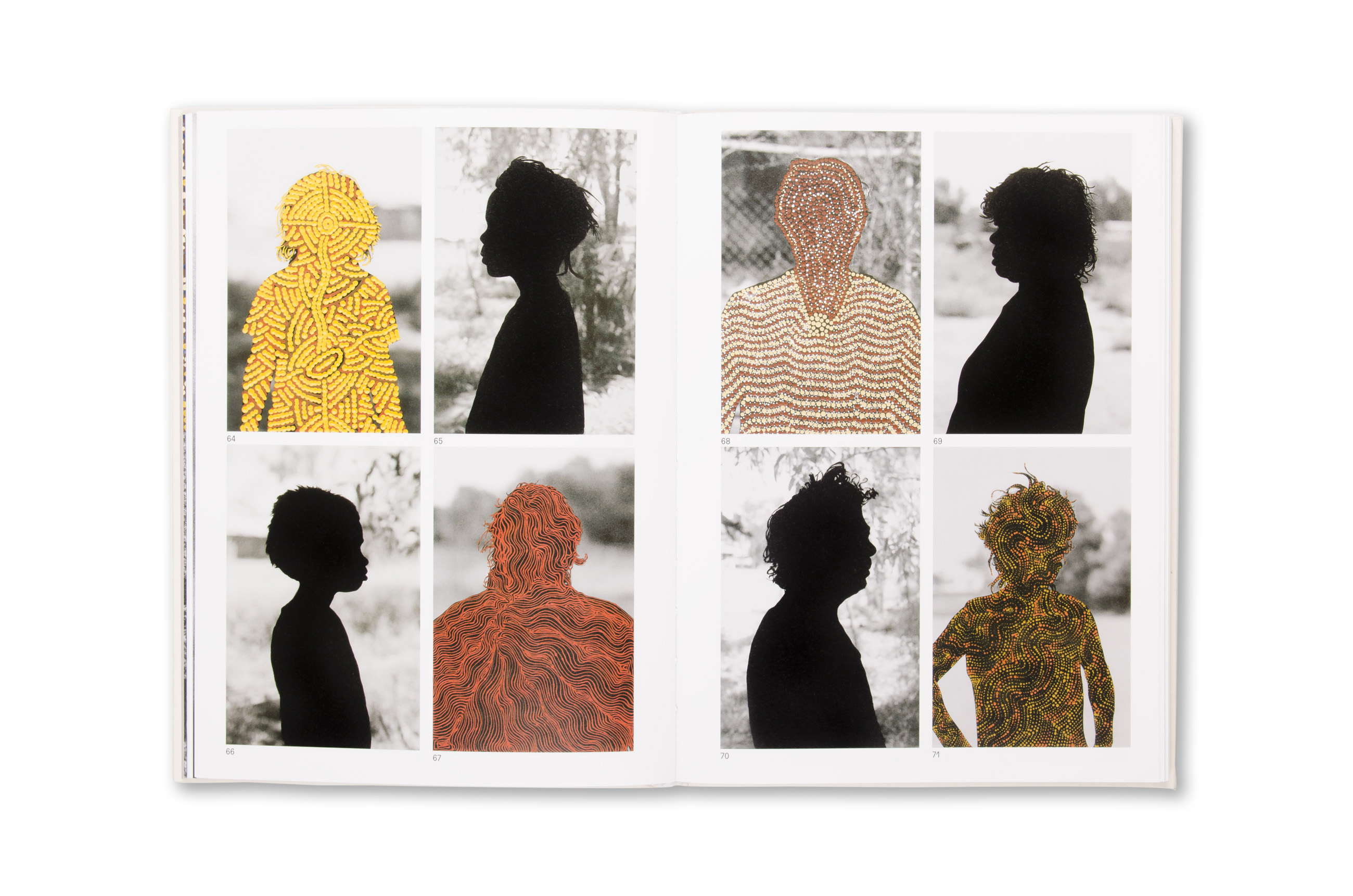

More than a century after Spencer and Gillen began their fieldwork, archives containing thousands of photographs and other artefacts dating back to the colonial era, have become largely inaccessible in institutions across Australia and Europe as attitudes towards them have changed. Images are often restricted with a black box placed in the middle of them to avoid showing pictures that infringe on Aboriginal beliefs. Even though the descendents of the people pictured can decide who is given access these images, much of the material remains locked away and unseen because the identities of subjects were not recorded, and therefore their descendants cannot be traced.

“I came across this phrase in archives on a regular basis – Restricted Images. Yet images were widely disseminated elsewhere. It felt like a metaphor for how people don’t really know how to deal with the historical record,” Waterhouse said.

Waterhouse’s

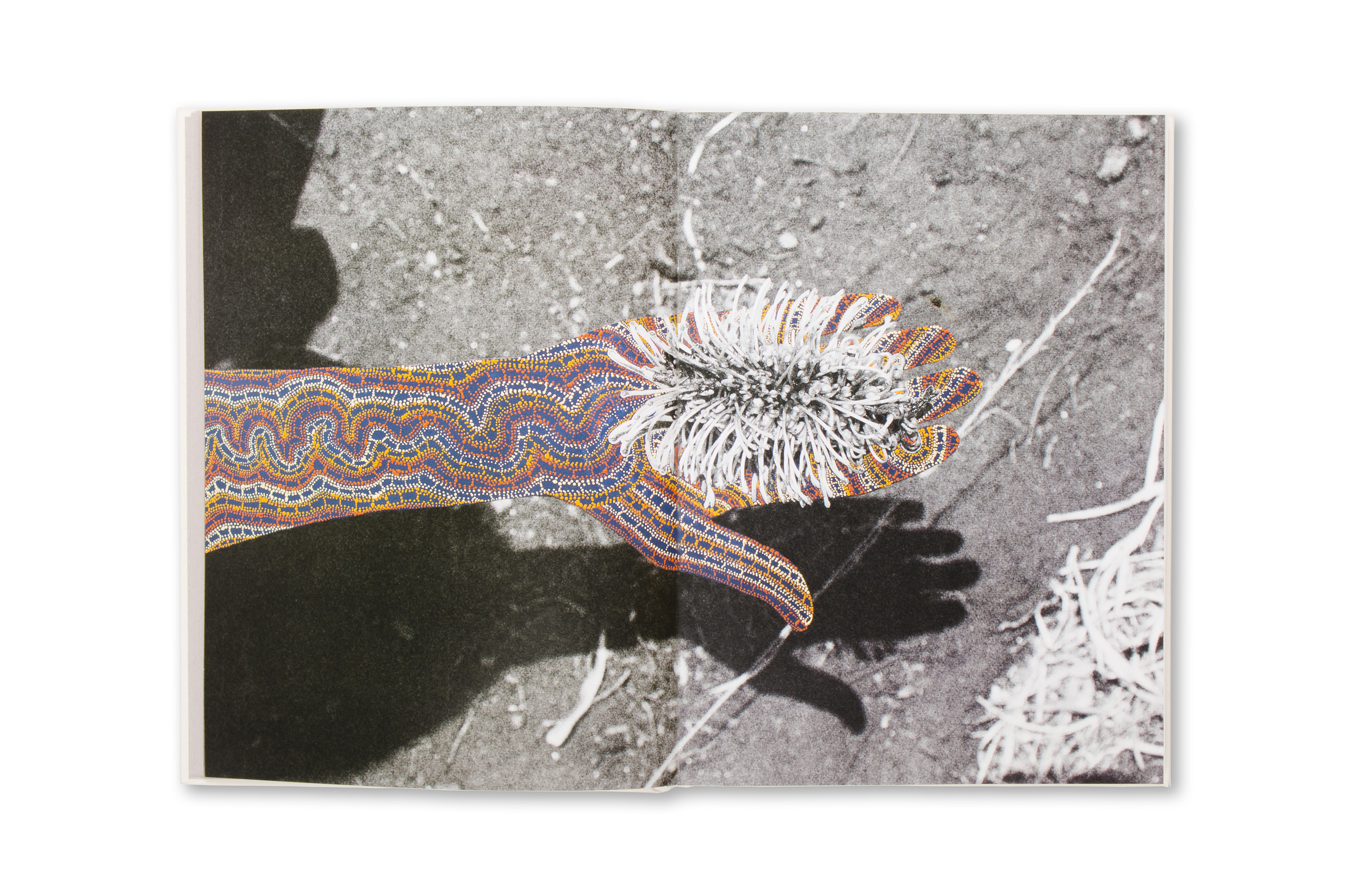

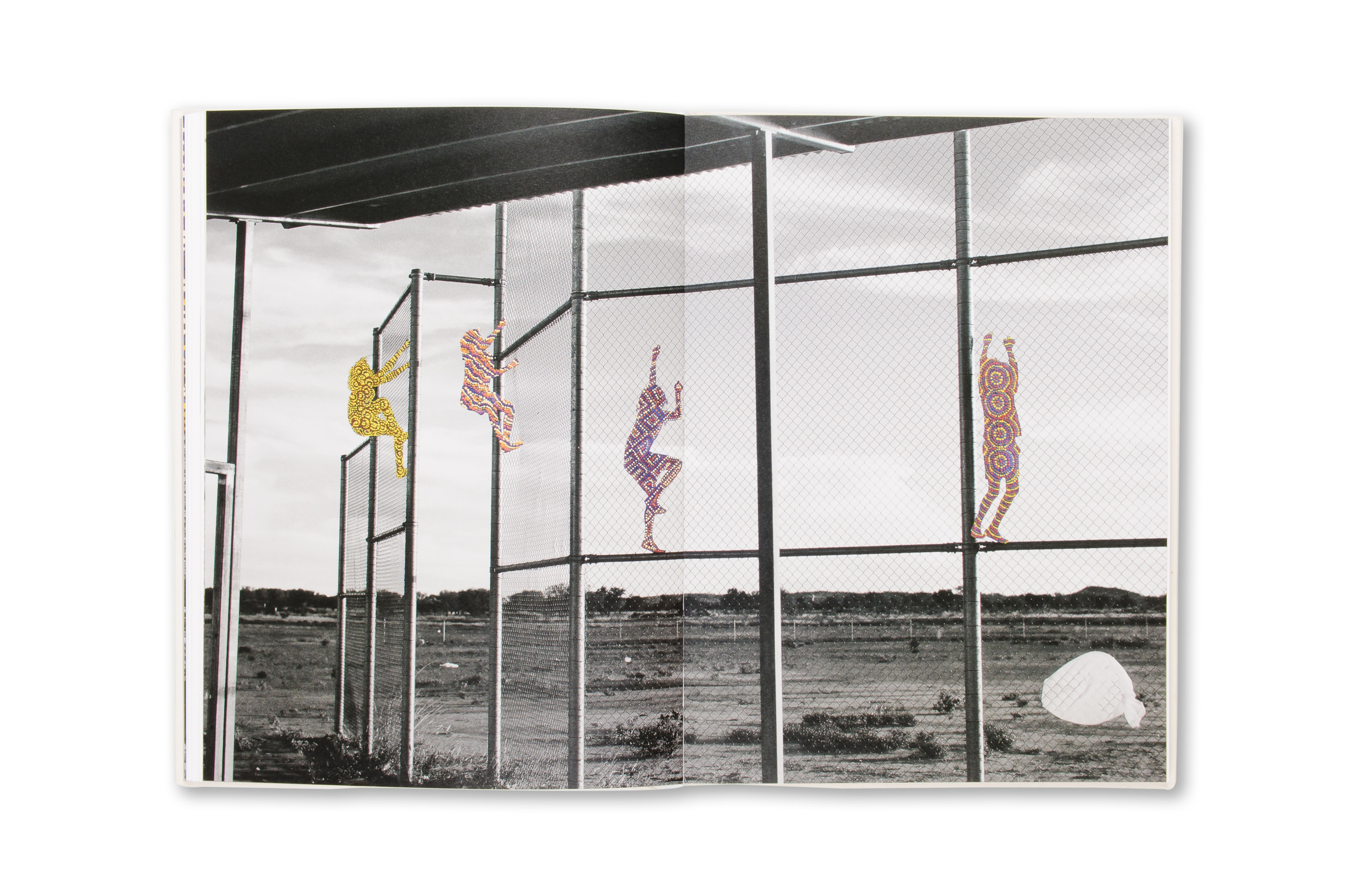

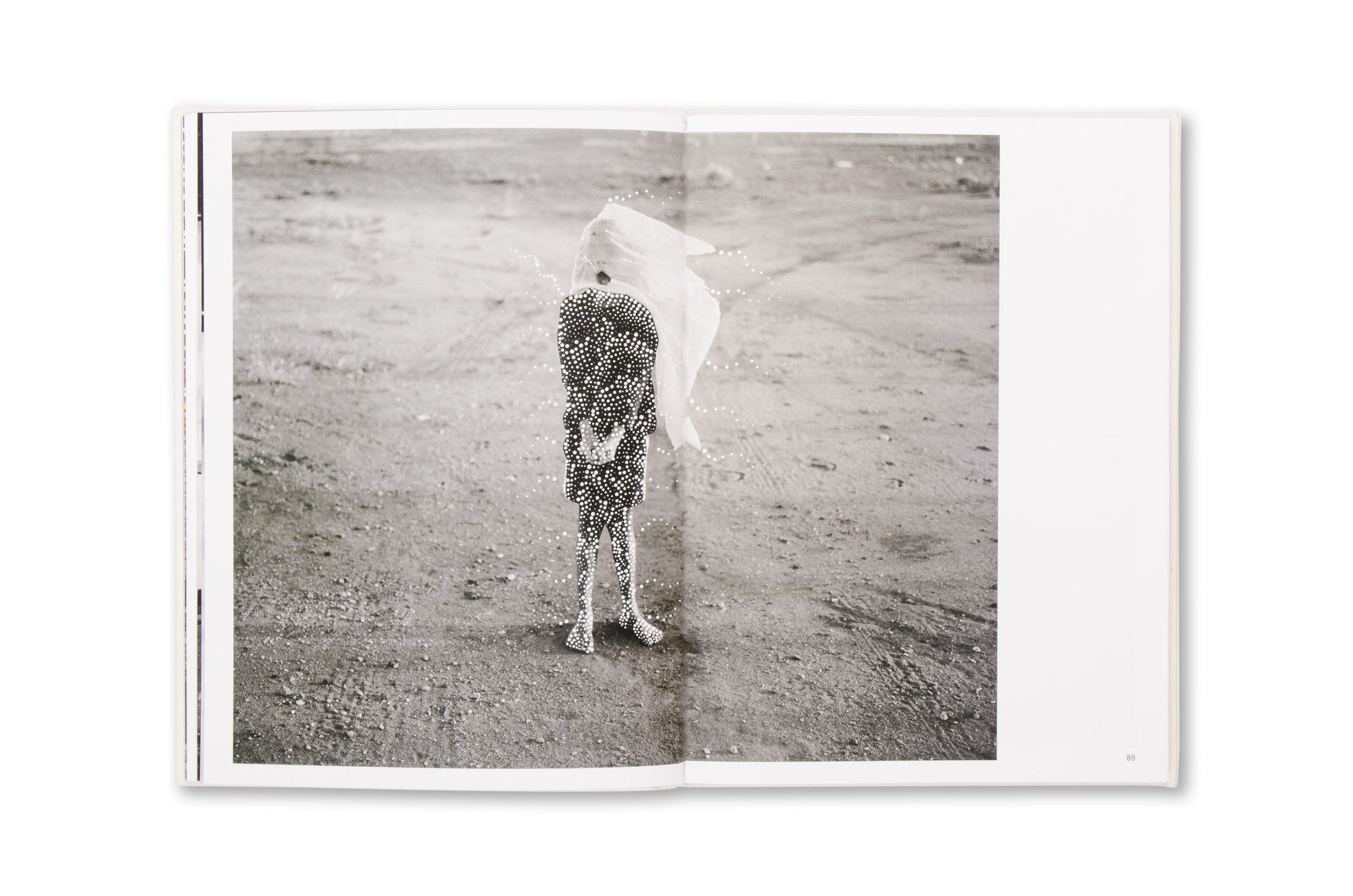

Restricted Images consciously plays with this metaphor by deliberately handing Aboriginal communities control over their own images. For four years, he worked with Warlpiri artists in Australia’s Northern Territory, taking pictures of them which he turned into black and white prints. The Warlpiri then painted over the prints, enacting their own restrictions using the traditional technique of dot painting.

“It’s another way of people having their identity but us not seeing their identity. Even the name itself [Restricted Images] speaks to whether people want or do not want to be seen, and what we have access to and what we don’t have access to, and who decides that,” Waterhouse said.

The artworks also acknowledge the importance of the Dreaming in Aboriginal culture. The term, which is not easily defined, refers to the story of creation, of how the stars were formed and how the sun came to be, of ancestor spirits who, once they had created the world, transformed into trees, rocks and other sacred sites. The Dreaming links ancient history to the present day and the physical world to the spiritual world. Expressed through song, dance, storytelling and dot painting, Dreaming stories still resonate among Aboriginal communities today.

For Waterhouse, the collaborative element of

Restricted Images was key to exploring the power dynamics of what gets seen, and also the unrecognized natural part of being an artist. “There’s a cult of lone genius in the art world, which is a lie that is in many ways told. But if you go back to any great work, it either speaks to another work or it was made, literally, with other people.”

The significance of Aboriginal art being showcased in a book published by a European company with links to the contemporary art world is not lost on Waterhouse. It simply adds to the debate about the politics of what gets seen, where and by whom.

“Aboriginal art gets put within the box which is seen as ethnographic and anthropological – and the contemporary art world shuns it for that reason,” Waterhouse said. “The process of making this work reframes it and brings it within an institution that in many respects rejected it.”